|

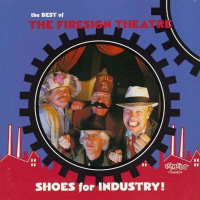

Shoes for Industry Available through Laugh.com Recurring Characters:Nick Danger, Ralph Spoilsport, George Tirebiter, Peorgie, Mudhead, Lt. Bradshaw, Catherwood, Nancy Category: Audio |

| Catalog (Flash) | Funway | firesigntheatre.com Home | Funway (non-Flash) | Catalog (non-Flash) |

| Previous: In The Next World, You're On Your Own | Next: Just Folks: A Firesign Chat |

| ||

| A best-of compilation drawn from Firesign's first nine albums. This is a good starting place for those new to Firesign who may want just a taste of what they're about, or as a great gift idea for introducing friends to firesign's unique brand of humor. It's also the only CD release containing their 7" single "Forward Into The Past / Station Break", previously only available on vinyl. |

| LINER NOTES: |

|

A self-contained four-man comedy troupe of writers/actors whose medium was the audio record, they created brilliant, multi-layered surrealist satire out of science-fiction, TV, old movies, avant-garde drama and literature, outrageous punning, the political turmoil of the Sixties, the great shows of the Golden Age of Radio, the detritus of high and low culture (James Joyce meets the found poetry of used-car pitch men) and their own intuitive understanding of the technological possibilities of multi-track recording. Their thirteen albums for CBS, recorded in various group permutations between 1967 and 1975, reveal them to have been at once the Beatles of comedy, the counter-cultural Lewis Carroll, and the slightly cracked step-children of Kafka, Bob and Ray, Jorge Luis Borges, Philip K. Dick, Stan Freberg, Samuel Beckett and the Goon Show. And as you'll hear when you play the album you now hold in your hands, they were also far ahead of their time, not just of it. In fact, while most self-consciously "hip" comedy from the late Sixties or early Seventies is as dated now as love beads and black-light posters (listened to Cheech and Chong lately?) The Firesign Theatre, satire - which dealt from the beginning with such unexpected subjects as the implication of cable network narrow-casting ("UTV! For You, the Viewer!") or New Age pseudo-philosophy (one of their albums was called "Everything You Know Is Wrong") - today seems eerily prophetic. In particular, the futuristic vision of Los Angeles - sprawling, fragmented, fear-ridden, multi-cultural, both low rent and high tech - that threads throughout their "oeuvre" (in particular their 1970 masterpiece, Dont Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers) is not only as poetically detailed as anything in Raymond Chandler, but chillingly on the money in 1993. Of course, the really important thing about The Firesign Theatre - the reason you've bought this compilation of some of their best stuff - is that they were (and are) hilariously funny. So where did these guys come from (or, as they put it in another context, "Who am us, anyway?"). Then, as now, the Firesigns - so named because astrologically speaking they were all fire signs - were Peter Bergman (born 1939 in Cleveland, Ohio), David Ossman (born 1936, in Santa Monica, California), Phil Proctor (born 1940, in Goshen, Indiana) and Phil Austin (born 1941, in Denver, Colorado). In 1966, they came together as part of a free-form, late night FM radio program on KPFK, Los Angeles, called "Radio Free Oz," hosted by Bergman in his persona as the Wizard of Oz. The format was "a late night talk show on FM just before FM got discovered," Bergman says. "It was on three or four hours a night," Austin adds, "and featured everybody who was anybody in the artistic world who passed through LA." Guests on the show did, in fact, include everybody from the Buffalo Springfield to representatives of the American Indian movement to Andy Warhol [who, Bergman remembers, refused to speak,] but the meat of the program was improvisational interaction by the group. "We each independently created our own material and characters and brought them together, not knowing what the others were going to pull," says Proctor. "And it was all based on put-ons; that is, we were assuming characters that were assumed to be real by the listeners. No matter how far out we would carry a premise, if we were tied to the phones we discovered the audience would go far ahead of us. We could be as outrageous as we wanted to be and they believed us - which was astonishingly funny and interesting and terrifying to us, because it showed the power of the medium and the gullibility and vulnerability of most people." The four Firesigns came to the show via a variety of circuitous routes. In Bergman's case, his led him from studying playwriting ay Yale (class of '61) to a stint in England where he worked on a program with legendary Goon Show alumnus Spike Milligan. The English experience proved fortuitous in another way. "I saw the Beatles in 1965," he says, "and right away I made a vow that someday I would have a four man comedy group, although we wouldn't dress alike. Which of course would make us more like the Rolling Stones." Once back in the states, "Peter drove down from San Francisco on his motorcycle," says Ossman, who had transferred to the station as a producer from WBAI in New York. "And during the station's first fund raiser he proceeded to be a sensation on the air, was immediately given the Oz show, and became a huge celebrity among the LA youth culture." Around the same time Austin, who was working in town as a stage actor, apprenticed at the station and replaced Ossman in the producer's slot when the latter took a day job in the programming department of ABC-TV (he continued to hang around the show at night, however). And finally Proctor - another ex-Yalie who was pursuing a successful stage and film career - discovered old classmate Bergman's new gig in peculiarly sixties fashion. As he recalls: "I was at this demonstration [ the infamous Curfew Riots on the Sunset Strip, later immortalized in the Buffalo Springfield's "for What It's Worth"]. And I sat down in front of this cafe on an open copy of the L. A. Free Press, and I relaized I was sitting on Peter Bergman's face - a picture of 'KPFK newsman Peter Bergman'. So I called him and got a part on the show." Originally monikered the Oz Firesign Theatre (by Bergman) the group later had to shorten the name when lawyers for Disney and MGM - who owned the Oz copyright - threatened legal action. Whatever they were called, however, the group and their freewheeling, sounded-stoned-but-wasn't brand of improvisational comedy were an immediate hit with the nascent underground audience. And as the Summer of Love loomed, they inevitably came to the attention of a record company, in the person of Gary Usher, trend-savvy producer for CBS and veteran of the L.A. surf music scene who had earlier done a comedy single - "Duckman, Parts I and II" - with Austin [ "Because I could do this duck voice," Austin says. "It was just stupid."]. Usher smelled commercial potential when he noticed 40,000 hippies at the first-ever Los Angeles Love-In in Elysian Park, which had been heavily promoted on the air by Bergman and others. The original idea was for the four radio celebs to make a "Love-In" (Bergman coined the word) album for Columbia. "And I said, 'no, let's do a Firesign Theatre album instead.'" Bergman says. Usher convinced Columbia to go for it, and the next thing the Firesigns knew, they were working for the most prestigious record company in the world. At that point, however, all they had was a title - Waiting For The Electrician or Something Like Him - which Bergman had developed "on the rooftop of an apartment in Amsterdam in 1965. It was for a terrible movie that was going to be done entirely in a dark room by matchlight. "We took an immense amount of time to write it," Bergman continues. "All of us come from theater or radio theater backgrounds, so we approached it as short plays with beginnings, middles and ends. The idea of writing plays for records seemed a perfectly good thing to do." Proctor recalls the group's working method thusly: "I would arrive late. And everybody would be angry with me. And I would say 'there's three of you and only one of me and why aren't you writing?' And they would all grumble and grouse and pour coffee. And then we'd sit down and catch up with where we were." "There was no leader," Bergman says. "Everything was communally written, and if one person didn't agree about something, no matter how strongly the other three felt about it, it didn't go in." This principle was to hold true with each subsequent Firesign effort because, as Bergman explains, "If one of us doesn't get it then something's wrong. But if we get it, then it doesn't matter who else does." All the Firesigns agree, however, that a mysterious synergy took place whenever the four of them got together. "It's like, suddenly there is this fifth guy that actually does the writing," Austin says. "We all vaguely sort of know him, and a lot of the time take credit for him." The album was recorded at the end of '67 at "CBS LA in their old radio studios, where countless CBS Hollywood programs had been broadcast" says Ossman. "Which was fitting, because we were the last generation of kids to be radio sensitive. We even used the original old RCA mics." "They had done the Jack Benny show from there, and a lot of others," Proctor says. "One day down in the basement we found all these old sound effects gadgets ... a prop door and marching feet and a wind machine, and we immediately incorporated them into the record. We were like kids in the candy store." Electrician, which came out in early '68, was technologically crude compared to their later work (depending on who remembers it, the album was recorded either on two-track, three-track, or eight-track) but still remarkably sophisticated for its day. Conceptually, it was a totally ground-breaking effort, taking on as it did such arcane-for-the-medium subjects as the way American culture had used the idea (rather than the reality) of the American Indian, and the inherent contradictions - mass bohemianism - of the hip culture that had nurtured the group. "We were making fun of 'the movement' right from the beginning," Austin says. "We never felt like pandering to the worst in any of it. But we never came across like assholes, I don't think, because we were ourselves very idealistic and very involved with the peace movement and all that." The centerpiece of the record - an 18-minute playlet conceived as a sort of tape loop - was the title track, a totally unprecedented slice of aural performance art which began as a Berlitz lesson and ultimately mutated into a Kafka-esque parable of nameless oppression. Proctor recalls that its genesis was a stage piece they'd done earlier, posing as members of a theater company that had escaped from Eastern Europe. "It was supposed to be some avant-garde play without words created by some fictitious European playwright, vaguely Polish or Yugoslavian," he says. "I remember that we pawned it off on this captive audience of students attracted by Peter's radio celebrity." Few people heard Electrician initially - depending on who you ask, it sold no more than 12,000 copies in its first year-but those who did knew they had encountered something unique. "There is nothing before 1968 that really presages Electrician, Bergman says with pride. "Sure, there are other audio pieces - by the dadaists and the pataphysicians - that were equally surreal, but they weren't dedicated to popular entertainment." "I think about what it was like when the audience heard it for the first time," he continues. "What a nosegay that was for well-educated people who wanted to laugh. Because the base of the material was intellectual ... it was college-boy stuff. And nobody had put that together and made people laugh in an audio way before." Having failed to set the world on its ear, the group continued to work on the radio and also began performing in folk clubs like the Ash Grove, often with blues acts like Sonny Terry & Brownie McGee. The rest of the time they prepared for a second album, although they had no assurance they'd be allowed to make one. "Columbia was going to kick us off the label," Bergman says, "so we scripted the next record and the old guard at Columbia took a look at the script and said 'This isn't funny - this is dirty!' And to our rescue came James William Guercio and John Hammond." "Jimmy Guercio was high enough up with CBS because of sales of the Buckinghams [which he'd produced], so he was able to get John Hammond [legendary discoverer of everybody from Billie Holiday to Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen] to take us on," Austin says. "With Hammond backing us up, CBS came around." Fortunately for the Firesigns, their sophomore effort - How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You're Not Anywhere At All - began to sell ("in reasonable numbers, not Dylan numbers" Bergman says), helped along, no doubt, by the fact that underground FM radio, by now a significant force, could actually play cuts as long as the Firesigns were creating. Recorded at the same CBS studios in early '69, How Can You Be was a noticeable advance over Electrician. The technology was improving while they worked - "We were getting more tracks to use as fast as we could make the album at that point," Austin remembers - which enabled the group to create the radio effects they loved with a new depth and realism. And the writing was equally assured. Side two, "The Further Adventures of Nick Danger", was a hilariously twisted take-off on the conventions of old radio detective shows (the original model, Austin hints today, was the Johnny Dollar program on CBS). The real mind-blower, however, was the title side, a seamless stream-of-conscious distillation of what Vietnam-era America felt like. Beginning with an ad for "Ralph Spoilsport of Ralph Spoilsport Motors in the city of Emphysema!" and some marvelously imaginative sci-fi effects (you actually hear the freeway signs coming by in the driver's mind), How Can You Be turned into a series of Alice in Wonderland vignettes in various exotic locales (featuring a W. C. Fields sound-alike), then segued into a deliberately unsettling old war movie parody (Babes in Khaki), and ultimately wound up with Proctor - who voiced many of the group's women's roles - doing the Molly Bloom soliloquy from ulysses as a guy. Even the cover was unusually droll - the group dressed as members of the Politburo under a sign hailing Marx [a picture of Groucho] and Lennon [a picture of John]. Clearly, this was not your average comedy record. Remarkable as How Can You Be was, however, it hardly prepared the group's now sizeable audience for the next Firesign Theatre release, 1970's Don't Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me The Pliers. Here, everything came together - the parodies of TV commercials and televangelists ("We had our knives sharpened for television on Dwarf," Austin says), the post-modern self-referential touches (you hear the other side of a phone conversation previously heard on Nick Danger, the mastery of sound effects and music (The B-movie takeoff, High School Madness, sounds astonishingly like the real soundtrack to some half-remembered Monogram youth film of the '40s). But what hit hardest for many listeners was Dwarf's unprecedented ending, in which the protagonist, old actor George Leroy Tirebiter (named after a locally famous dog who used to chase cars at USC) wakes up in front of his TV all alone on the top of the hill in sector R, then dashes out to chase a stray ice cream truck, his voice trailing off into childhood as he fades into the distance. By this point, of course, people expected funny from the Firesign Theatre; inexplicably moving was something else completely. "Dwarf was our first saga," Bergman says. "When we did it, we were so involved in it that we didn't have a sense of it in its entirety, but when it was finished, I remember listening to the playback and feeling very moved by it, thinking it was quite wonderful." "With Dwarf the form of the album became very interesting to us," Ossman adds. "The first album was essentially a comedy album, it had cuts on it. The second album had evolved from our radio show and a stage piece. So Dwarf was our first piece really written right from the beginning for this forty-minute thing called a record album. We knew it had to be more than a series of comedy sketches." "It's the first piece of ours that's long enough to be essentially a one-act play," Austin agrees. "The idea that we continue it from one side to another, and turn the record over and drift through the hole in the center, and think of it almost pictorially is to me the big leap of faith. Plus Dwarf to me is the most human of our early records. It has a main lead character who, unlike Nick Danger, is a reactive human, not a guy who makes his voice do things. George is like a real person." Part of the reason Dwarf turned out so well was purely technical: it was the first Firesign Theatre album recorded on 16-track. And because of a contractual tradeoff - the group got a ridiculously low royalty rate but unlimited studio time - they were able to keep doing things until they got them right. "It was the time we felt most relaxed about going anywhere we wanted to with audio," Bergman says. Ossman remembers that "Dwarf was done with the original Dolby machines. "They rolled them into the studios and said 'this might help you guys.' Because with all the overdubbing we were getting so much trouble with tape hiss." "The unlimited studio time allowed us to write while we were working," Austin says. "And by Dwarf we had really gotten to feel comfortable with the process. It allowed us to experiment with the sounds of things. Technically, we understood we could use Hammond organ horns and run voices through them, or use backward tapes." This seems to reflect the influence of Bergman's original inspiration for the group, the Beatles, and Austin is quick to confirm the perception. "The Beatles were a huge influence on The Firesign Theatre," he says. "This was a period when we were doing large amounts of references to current Beatles product, and playing with the idea of using a whole album and tying the cuts together and using the more avant-garde audio techniques. They were far ahead of us when we started, but with our words and our own material, I thought we caught up real fast." Dwarf's success was not without its down side, however. "During that period we began to be self-consciously 'The Firesign Theatre,'" Bergman recalls. "We toured after Dwarf and we began to realize the extent we were influencing people. We realized that FM radio was playing our albums whole, and that people were memorizing them. I heard stories later, for example, that at MIT they wrote the entire script for Electrician on the walls of the main building." Austin agrees that the new respect the troupe was receiving was not particularly beneficial. "At that point we began not to get along with each other that well," he says, "and the being taken so seriously - Rolling Stone did a long article on us, and we were being compared to James Joyce - there was a prideful attitude that took over. But we weren't making money; we might as well have been teaching school somewhere and worrying about making tenure for all the money we were making. So in some sense we didn't really understand what we were doing, which is why we were never able to make a second Dwarf, which to me is a real disappointment." The next album, 1971's I Think We're All Bozos on This Bus, picked up literally where Dwarf left off - with George Tirebiter chasing the ice cream truck - and then went on to anticipate such concepts as Star Trek's holodeck and interactive computers. Commercially it fared well, but it was artistically disappointing after what had preceded it." "Bozos was written exactly as it exists more than any of the other albums," Ossman says. "The idea of it was based on a combination of the magic and characters of Disneyland and the City of the Future from the '39 World's Fair. We did a lot of historical research for it. The word bozo comes out of 1933, and we restored it to the language." "Bozos I always thought was a little cold," Bergman says looking back. "Parts of it I quite like, but I always thought it didn't have as much heart as Dwarf. But it was more presentational, and in that sense it really brings to a close the first period of the Firesign's most imaginative work. "It sold a lot of albums real quickly," he continues. "But when it was done we were faced with 'what do we do now?' It wasn't making our fortunes. And it burned us out, because we were writing five days a week." Not surprisingly, the group's reaction was a period of retrenchment, beginning with the 1972 double album Dear Friends, a collection of bits from their radio shows, and continuing with 1973's Not Insane, which most fans felt had only flashes of the Firesign's trademark wit. Neither helped the group's commercial momentum particularly. "Dear Friends was an attempt to get airplay," Ossman says bluntly. "We felt that it would be clear to everybody that this was a radio album, one that would be just jokes and funny stuff. I think there was some perception that this wasn't a major Firesign opus, but I don't think it was as damaging to us as Not Insane, which was a serious mistake." "Not Insane was when the Firesign was splitting apart," Bergman says. "it was a fractious, fragmented album." Ossman is more dismissive. "In retrospect, it was incomprehensible, basically. Although some people with their eyes spinning have told me 'this record saved my life.' in any case, it was not the album it should have been and I think that caused us to slope off rapidly in sales." The next step, predictably, was a faux rock group move - solo albums. First up were Ossman's How Time Flys and Proctor and Bergman's TV or Not TV, both in 1973. Austin countered in '74 with Roller Maidens From Outer Space, and in '75 Proctor and Bergman returned with What This Country Needs, a live album reprising bits from earlier records, including TV or Not TV. All of them had their moments, and all the group members appeared on them in some capacity, But they weren't as good as Firesign Theatre records, and everybody knew it - including The Firesign Theatre. "The solos weren't a bad idea," Austin says, "but they diluted the group impact. Part of the problem was there was never anybody else to play with. I'm not a musician; if I was going to do a solo album I couldn't go off and play with the Allman Brothers." "I tend now to be more forgiving of the solo work, including my own," he says. "But we all naturally suffered from the fact that we weren't re-writing each other's shit as ferociously as we would have in The Firesign Theatre." Ossman has a different perspective on the solo records. "They seem to me to make another opus ... the record we didn't write that year. There was a breakdown in group communication. But I felt that the solo work could be very fruitful, that we could continue doing Firesign Theatre albums once a year, and we could also spin off." Ossman also feels that there were legitimate artistic reasons for the solos. "We were disagreeing about focus. I wanted more storyline, Phil Austin wanted to explore the detective noir hero in a less frivolous way, and Peter and Phil wanted to do a deal with the world of TV, which they saw through to cable - 'One man, one channel.' Which in 1973 was really forward-looking, as well as being funny stuff." During this period there were also three "real" Firesign Theatre albums, at least two of which were on some level returns to form. The first was by far the sunniest album they had ever made, an often uproarious, 1974 Sherlock Holmes parody called The Tale of the Giant Rat of Sumatra. Ossman: "When we came back together after having not worked together for a year, the one piece of material we had that we could all agree on was Giant Rat. Not the story, per se, but the Hemlock Stones character which we had done on radio. The American characters were from a parody of Republic Serials we had done on stage. I always thought it was the closest thing to the relentlessly pun-filled one-acts we did in clubs." Austin is less thrilled with it. "The Sherlock Holmes album didn't do anybody any good," he says. "The general public was by that point beginning to tire of psychedelia anyway, and we were unfortunately always going to be associated with that." Bergman seems to agree they were becoming out of step with their audience. "Giant Rat did pretty well," he says, "but things were beginning to shift. Nixon was out of office, people were putting on white suits and pointing in the air and disco dancing. The Vietnam war was over. The Seventies were the Eighties, people forget that. That period of greed began in the Seventies - the public greed, the 'let's burn as much as we can'. The Firesign theatre knew there was a shrinking atmosphere for us, because people were less and less questioning the big show...they were buying it." The Firesigns followed up in 1975 with Everything You Know Is Wrong, a New Age/UFO/aliens-among-us spoof that is perhaps the last record where they seemed to be genuinely enjoying themselves. "The whole experience of Everything was fun," Austin says, "like a big deep breath. My favorite thing about it is particularly the stupidest thing about it ... the confusion between fried eggs and flying saucers. I just love that kind of simpleminded, half dumb, half smart humor that the Firesign Theatre can project." "Everything grew out of our basic interest in those parapsychological things," Ossman says. "From Castaneda to the hollow earth theory to the guy who bends spoons. Originally, when we started writing it, it was going to be a much more complicated and 'cinematic' record; we were trying to write a radio movie." In fact, after it was finished, the Firesigns shot a full-scale movie around the record, with cinematography by the young Alan Daviau, who went on to film Spielberg's E. T. Fun winding down, the last official Firesign Theatre album on Columbia (not counting a greatest hits compilation, Forward Into The Past released a year later) was In The Next World, You're On Your Own, also from '75. Actually, it wasn't a "real" Firesign album; Austin and Ossman wrote it and then Proctor and Bergman , who were touring during its inception, came in essentially as voice talent, although they gave their parts considerable polishing. Nobody in the group has much to say about it today. "It's steeped in commercial sex and random violence, very dark," says Ossman. "It's a little more fiery than the other solo albums," Austin comments. "But we didn't have a happy Phil and Peter at that point." Not surprisingly, when Columbia declined to renew the Firesigns' contract after the negligible sales of Next World, the group didn't make an issue of it. "We didn't fight," Bergman says. "The group had really split apart; we had just burned out. I mean it was five years non-stop work. We would stop one album and start writing the next. Frankly, we didn't have five more albums in us at that point." "Being dropped was disheartening," Austin says. "But on the other hand we had become used by that time to having doors slammed in our face as the world began to disco down. The world that we had grown up in artistically began to be sort of pulled out from under our feet, and we were smart enough people to understand that we were going against the flow and that it was probably logical that these sort of things would happen to us." Post Columbia, the group was hardly dormant. There was a series of albums on other labels (Fighting Clowns, Just Folks, and a new Nick Danger effort called The Three Faces Of Al) and they continued to write and perform elaborate stage shows. "We were very disappointed at not being able to do a Bicentennial album, which would have been a significant American occasion for us," says Ossman. "And during this time we tried television, and we wrote a move which foundered on the glistening rocks of cocaine on the one hand and on the other that MGM fell apart." Finally, Ossman quit to take a job as producer at National Public Radio - "it was too good to turn down," he says. "And it wasn't as if I was abandoning The Firesign Theatre, because there was nothing really that we were doing. MTV was destroying people's already limited attention spans, Reagan was in, and it was time to hustle." He was soon fired for a program honoring John Cage's seventieth birthday. "Phil and Peter and I kept working," Austin says. "We made The Three Faces Of Al, which finally got us nominated for a Grammy. We didn't win, but Weird Al Yankovic got on stage and thanked us, which was really sweet." The trio continued through most of the Eighties; they did midnight movies ("J-Men Forever"), video specials for Cinemax and Pacific Arts, and even got involved in an elaborate CD-Interactive program. But eventually, Austin realized he hadn't spoken to his former colleagues for two or three years. It seemed like the curtain had finally fallen. But all that changed this year - specifically on April 24th, at a wildly successful reunion show of the four original Firesigns in Seattle, where jubilant fans ranging from Night Court's Harry Anderson to Pearl Jam drummer Dave Abbruzzese were glimpsed along with 2,900 others. "I dreamed it back," Bergman says proudly. "Sure enough, when we kicked the fascists out of office it was time for The Firesign Theatre to come back." "I was working on a novel and a screenplay for the Grateful Dead," Austin laughs, "and I had faced the fact in my mind that I was never going to have to deal with The Firesign Theatre again. And suddenly we did this show..." "The audience was just like 1974," Ossman says incredulously. "Apparently, the time is right ... there was something about the Eighties - the anti-surrealist politics of the Eighties - that was wrong for The Firesign Theatre. But now there's a change in the climate." As of this writing, the group is preparing a 10-city tour; it will be taped for a cable special (to be shown, most likely, on HBO or Cinemax) and negotiations are currently under way for a brand new album, titled The Illusion Of Unity, for major-label release next year. I never thought the Firesign Theatre would be over," Bergman says. "And when we go on the road, as far as I'm concerned, it's not nostalgia - it's the return of comedy theater, which is a great American tradition. When's the last time a comedy theater came to your town?" Bergman also believes the group has serious unfinished work to do. "Our best albums, although we were never overtly political, had a theme underneath them - the War. And when the War was over, we lost our theme. But I think we have one now, which as I see it is about America's long period of denial - the fact that we have to change." I always thought that what we were doing was way too artistic for the medium," Austin says, "that it would never be commercially successful. So when we had some commercial success I was totally shocked, and am to this day." "I'm real proud of The Firesign Theatre," he concludes, echoing the sentiments of the entire group. "Right from the beginning it's always been more of a labor of love than anything else." By Steve Simels Stereo Review |

| Display All Firesign Items By Category |

| Catalog (Flash) | Funway | firesigntheatre.com Home | Funway (non-Flash) | Catalog (non-Flash) |